For refugee children from B&H school is also a "game"

Schools in Una-Sana Canton were the first to open the door to refugee children from Syria, Iran, Afghanistan, Iraq and other countries. It was a shock for everyone, for residents of Cazin and Bihac, for educators, and for refugee children.

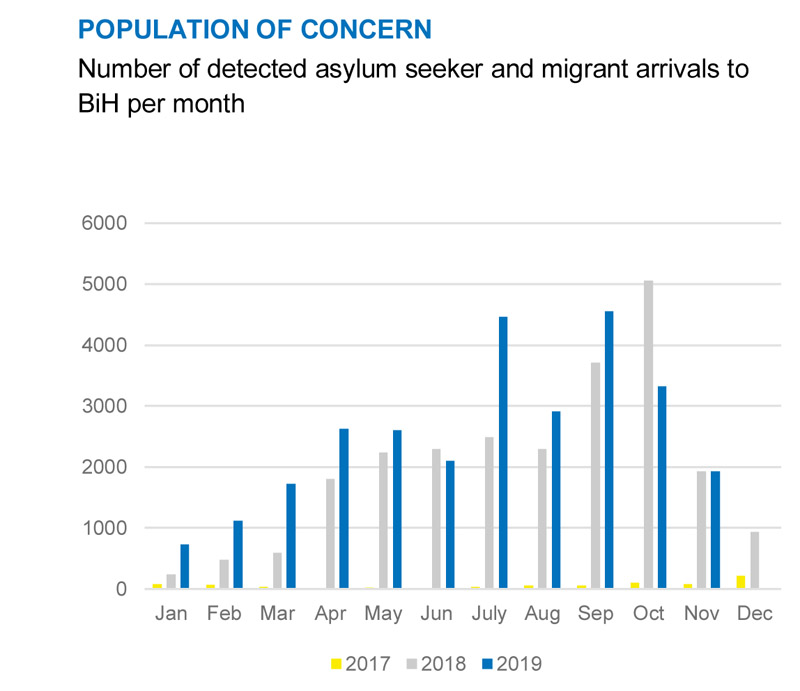

Bosnia and Herzegovina later faced the problem of refugees from the Middle East compared to Serbia. Trying to make their way across the border of Serbia with Hungary or Croatia, BiH became part of their route in 2017, only for about 200 of them. Over time, the number increased, so that in 2018, some 24,000 refugees came to BiH, and slightly more than 28,000 during 2019.

About 6,000 of them stayed in a total of six refugee centers throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina. In Una-Sana Canton alone, there are four centers, two family centers with about 200 families, two for singles and unaccompanied boys. Thus, since the second semester of last year, around 150 children have gone to school with the help of UNICEF, mostly in this canton and slightly less in Sarajevo Canton. This year, according to UNICEF, this number is down nearly two-thirds at the start of the school year.

We are good students, we learn a lot

Thirteen-year-old Donia is overjoyed to be going to school. Her love since childhood was math, though it only took her two months to learn Bosnian. She's diligent learning all the subjects, but when she could choose, she would only do math. She says that is logical, because she comes from Afghanistan.

"When I go to Germany one day, I'll be a math teacher," says this charismatic girl with a smile. Her mom explains that whenever Donia is sick, she cries because then she can't go to school. She says that she watches her prepare books for lessons with a smile and joy. It makes her very happy.

Donia at the "Borici" Refugee Center in BIHAC, © Sasa Djordjevic

For Hasan from Azerbaijan, who is only one year older, the material is harder, especially physics because it is in Bosnian language and therefore he could hardly understand it. German also and especially history is hard for him. This is because it teaches the history of the Balkans during the Ottoman Empire. Do they need it, we ask them and Donia's mom, Osita Nasimi.

Donia and Hasan say they are hardworking because that is how it should be and that they are great students, and Osita explains that all the knowledge they gain on their journey to Germany is of great importance. "On our way to here we have also been to Turkey, Bulgaria, and Serbia. She did not go to school there, but she learned Turkish, and a little bit of Bulgarian. Everything we collect along the way is very important to us for the years to come,” Osita explains.

As this is a new experience for everyone, schools and teachers also found themselves in a special situation. In collaboration with UNICEF and Save the Children, an adapted HEART learning method was created, namely Healing through art. Teachers use this methodology in preparatory classes where it is essential to learn the language and Latin script.

Edina Mehic from Prekounje Elementary School in Bihac is a pedagogue and coordinator between the school and camps where children are housed on one side and UNICEF, Save the children and the Ministry of Education on the other. In addition to the new methodology that is applied to refugee children, a study visit to Serbia was of great help to them, when they were able to learn from the Serbian colleagues about the challenges and difficulties in working with new students.

First language, and then real school

"When they have mastered Bosnian enough, there are some tests that assess whether children are ready to engage in a regular educational process with other Bosnian children. The duration of this process is individual, it depends on the child - if the child was already in a school in Serbia, he or she had already learned a language, we have similar languages, letter, that child can be included in the educational process in a few days. And if a child comes from some Middle Eastern country, it's a completely different letter, a different culture, then we need a little more time, but in principle no more than a month or two, after that, the kid is ready to go to school," educator Edina Mehić says.

Leisure activities at the "Borici" refugee center in BIHAC, © Saša Đorđević

There are three age groups in which refugee children are educated, from 6 to 9 years, from 9 to 12 and from 12 to 15. During the first semester, 60 students passed through the Prekounje school in Bihac, the educator of this school tells us, because they constantly come and leave trying to cross the border with Croatia.

While in school, all subjects are taught in Bosnian. Edina Mehic says that a lot is worked with them related to geography and history, and most on ecology. She and her colleagues have noticed that children are most interested in mathematics, and she thinks that this is due to the fact that mathematics is in the universal language. However, when a language problem arises, cultural mediators who come with children are of great help.

"Cultural mediators know the languages of children, and when the problem arises, when the teacher cannot explain the children what is expected of them, then they explain to the children what their task is. They were recruited by Save the children and UNICEF and they are a great help to teachers in overcoming this language barrier, which is huge at first. Later, it gets easier and easier, ”Mehic explains.

A Bosnian teacher at Harmani 2 in Bihac, a school that also opened the door for refugee children among the first, said she was afraid of that language barrier at first because she said that in the University she was not educated to teach foreigners Bosnian, only native speakers. Brochures from colleagues from Serbia and Croatia helped her a lot, and later they made their own brochures. She especially prepares for classes where she has children from refugee centers, but that does not bother her.

"Just so there would be no war "

"It really takes a lot of effort, but it's not difficult because you get feedback. These are the kids that are on the move, they often go, as they say, "to play", trying to cross the border. And more often, they come back. And whenever they come back, they are back in school, again with a desire to learn. Realistically, they don't need Bosnian, they don't want to stay in Bosnia, but they want to learn it, "explains teacher Nermina, who took her role very seriously, especially because she feels that she "owes debt because of her daughter being educated abroad, with some other people taking care of her."

She tells us an anecdote with the students who asked her that as they learn her Bosnian language, she learns their language, Farsi. It was difficult for her to utter their words, creating even more enthusiasm for new students, because, as she says, these children have an incredible will for knowledge. She says that she has been involved in the schooling process for refugee children since January 2019, but that she first met them a couple of months earlier when she visited the first family center in Bihac with the children from the journalism section she runs.

"At that time, we were preparing a school event for November 25th, National Day, and a recital "Dohvati mi tata mesec" and somehow it seemed convenient for the children who were attending Bosnian at the refugee camp at the time to prepare this recital together with the children from schools. We didn't tell anyone about it. An Afghan boy asked me if he could sing a song. I said I couldn't promise, let him come, he would be a guest, but if there was room at the event, he would sing. Of course, the parents also came with the children, they were all our guests, ”the teacher says, adding:

"It was a surprise for everyone in the hall, what is happening now, who are these people. When the kids came on stage, hence one migrant refugee kid, one kid from our school and they started reciting a song in Bosnian together. There were children there who did not speak Bosnian but had a desire to learn the song, and they learned it by heart to be part of the story. The applause was thunderous. And long. At the end of the show, there was room for the boy to sing the song, and the song was "Just so there would be no war". Everyone was crying, ”she says.

These touching moments, unfortunately, were not felt by all school-age refugees who found themselves in BiH. Unlike Bihac, which is located in the Una-Sana Canton and Sarajevo, which is the main one in its canton, the children in the refugee center in Mostar do not go to school because the decision was made at the level of the Herzegovina-Neretva Canton.

All levels of government, a total of 4 levels, where the first two are the state level, then the entities or cantons, which are independent of each other, so the cantons base the legislation on the state, but each canton changes them as they wish. This creates a major problem for UNICEF, which cares for the education of children, but also for organizations gathered around UNICEF.

"I cannot say why the state institutions made such a decision," Amila Madzak from UNICEF tells us, adding that negotiations with the cantonal ministry of education are taking place in order to change that.

"In Salakovac (Mostar), our implementation partner is World Vision, where we also have child friendly spaces, where children have different non-formal education, different educational activities, learn Bosnian and English. But it's all informal. All children should go to school with other children because this is their fundamental right, ”Amila Madzak told MIC.

"We have children of 11 years who have never gone to school"

In the center of Salakovac in Mostar, at the time of the MIC visit, there were about a little less than 50 children between 6 and 17 years of age.

"If it was only one child it would still be important, and there we have 47 children who live in Salakovac and do not go to school. It's a huge loss. They spent all that time, while on the road, without school. Some went to school in Serbia, some did not, because they started the journey when they needed to start school, so we have children who are 11 years old and never went to school. They don't know exactly what it looks like, "Madzhak explains.

Refugee children in Mostar have no school activities, © Sasa Djordjevic

All refugee children around Mostar have a lot of free time that many organizations try to fill with different activities.

Aldina Media is the Coordinator of the BiH Women's Initiative Foundation, which, with the support of UNHCR, provides various types of psycho-support services for families at this center. They are also implementing a project called "My School" for school-age children. As they hope that the decision of the cantonal authorities changes and that the children who are accommodated in Salakovac will eventually start going to school, the children learn Bosnian daily, as well as other subjects that they would have in formal education.

A lot of empty space during one day is further enhanced by the attitude of Mostarians towards refugees, as well as the distance from the city. Unlike Bihać, where the villagers do not have a negative attitude towards refugees, there were negative comments among people from Mostar about the education of refugee children. Also, the Salakovac refugee camp is ten kilometers away from the city, so people from the camp near Neretva are rarely seen, compared to those near Una. Therefore, refugees in the center of Salakovac can only spend their free time in their closest environment, with almost nothing.

Unlike the number of children within families, the number of unaccompanied minors is significantly more difficult to track. Some of the migrants are not accommodated in refugee camps at all, but pay for their accommodation themselves. According to UNICEF data, in October there were 200 unaccompanied minors in the Una-Sana Canton alone. The exact number of high school age children is unknown for the same reason.

As for the education of high school children, Madzak says there are more obstacles at stake. "One of them is financial. Other reasons are practical and technical - in order to enroll in high school, you must have documentation that you have completed elementary school. And besides, you have to pass the knowledge test. None of this is completely achievable for them, it is very difficult for them to pass the knowledge test, and few have documentation of completed primary education. These are obstacles. But they are not insurmountable, just as we were able to adapt primary school teaching to children, we believe it could be done for high school, too, ”she said.

And do the children get the document that they have finished elementary school in B&H if it happens? Amila Madzhak says children can get proof, however, few parents ask for it. "They get into the “game” all the time, few succeed, but when they do - that's it, it happened. They left, without bringing any evidence ".

For more photos click here

Author: Jelena Djukic Pejic

Translation: Mladen Djordjevic